Dear Friends: While I was in Mexico last month, several of you sent me the link to the tragic story in the New York Times of the 12-year old Cañari girl, Noemi Álvarez Quillay, who hung herself in a children’s shelter in Juarez, Mexico, after being caught trying to migrate to the U.S. (www.nytimes.com/2014/04/20/nyregion/a-12-year-olds-trek-of-despair-ends-in-a-noose-at-the-border.html) Her parents, undocumented immigrants living in the Bronx, migrated north when Noemi was a three, leaving her to be raised by her maternal grandparents, along with four young cousins left by other family members. A few months ago, Noemi’s parents arranged with “coyotes” to bring their daughter to the U.S, paying from 15-20 thousand dollars. These arrangements were made from New York through a vast human smuggling network that begins in the village where Noemi lived and extends through Central America, Mexico and the border city of Juarez where she died. Little is known about how she traveled – some deals involve flights to Mexico from Ecuador with false papers; others begin in Guayaquil on rickety fishing boats that arrive 5-8-days later off the coast of Guatemala, and migrants go overland from there, traveling by bus, truck and on foot through Central America and Mexico.

Noemi had been sent once before, a year ago, and – as she wrote in a school report – a school report! – she was detained in Nicaragua for two months before being sent back. She was only 11 then. Although I know many migration stories, I simply cannot imagine this girl – or my 11-year- old grandson, Cosmo, for that matter – leaving home alone on a dangerous journey, with strangers, detained for two months in a strange country, and sent back home.

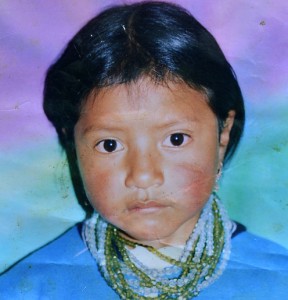

From this creased photo published in the Times, I’d guess Noemi was seven or eight when it was taken, as a school ID photo. The article included a quote by her grandmother when Noemi’s mother told her she was sending for her daughter: “I said to her, ‘Why take her away? She’s studying here, she’s doing well.’ But my daughter says education in Ecuador is no good and it’s better for her to study there. And she took my Noemi away, only for this to happen.”

One month and 4000 miles later, Noemi was picked up in Juarez and taken to the shelter, Casa de la Esperanza and interrogated by a prosecutor, who was probably going after the coyote (in whose truck she was found). Noemi was reported to be terrified and crying inconsolably for a few days before she locked herself in the bathroom and hung herself with the shower curtain. An autopsy report showed she had not been sexually abused – an all too common crime against migrants that thankfully she was spared.

I suspected when I first read the article, and confirmed once home in Cañar, that Noemi was from a village I know well, not far from where I live (I don’t know the family, though their name is a common one). This past week I visited the country school where Noemi might have been an 8th grade student next year. I went to talk to the junior and senior girls about our scholarship program that sends low-income Cañari girls to university. “Ninety percent of our students are affected by migration,” Principal María Juana Alulema told me beforehand. “One or both parents are gone, and they are left in the care of grandparents, aunts and uncles, or others. As our students get close to graduation, all they can think about is migrating north. They do not concentrate on their studies.”

Below: Sisíd bilingual secondary school (Spanish/Quichua), for 9th -12th grades. Principal María Juana Alulema and the senior girls.

Principal María Juana Alulema and the senior girls. Still, in my talk with the girls I tried to present an option to migration – showing them photos of our present scholarship women and graduates, saying they were also poor and from similar communities, describing their determination and difficulties in getting through university, some while marrying and having children. I listed their professions: Pacha, dentist; María Esthela, Transito and Marta, nurses; Mercedes, lawyer; Carmen, economist; Juana, veterinarian; Luisa, physician.

Still, in my talk with the girls I tried to present an option to migration – showing them photos of our present scholarship women and graduates, saying they were also poor and from similar communities, describing their determination and difficulties in getting through university, some while marrying and having children. I listed their professions: Pacha, dentist; María Esthela, Transito and Marta, nurses; Mercedes, lawyer; Carmen, economist; Juana, veterinarian; Luisa, physician. I also mentioned to these high school girls what they already know well: their jobs in the U.S. would most likely be limited to hair or nail salons (like Noemi’s mother), cleaning hotel rooms, working in restaurant kitchens, stitching clothing, and so on. Migrating, in almost every case, means the end of educations.

I also mentioned to these high school girls what they already know well: their jobs in the U.S. would most likely be limited to hair or nail salons (like Noemi’s mother), cleaning hotel rooms, working in restaurant kitchens, stitching clothing, and so on. Migrating, in almost every case, means the end of educations.

It was hard to read their responses (as you can see from the photo). But I gave the girls application forms and invited them to come see me and learn more. And I’ll go again next year, and the next, until we have a scholarship woman from this village.

In the week after Noemi’s death, 370 foreign child migrants were detained across Mexico, according to the national immigration agency. Nearly half were traveling alone. From the article: The number of unaccompanied minors caught entering the United States…is expected to reach 60,000 in the 12 months ending Sept. 30, an increase from 6,560 in 2011.

But to return the the theme of education, I’d like to end with the story of another Noemi, the daughter of one of our scholarship graduates – Pacha Pichisaca, now a dentist with her own practice in Cañar. In the photo below, Noemi is the little girl on far right, looking straight at the camera, playing with other “scholarship kids” in the patio while their parents met in my studio. (“Keep ’em out of the fountain,” I can hear Michael saying. Impossible!) Noemi is six or seven now. Her parents came from poor indigenous families that chose not to emigrate. Her father, Juan Carlos, a professional musician and teacher, and her mother Pacha married during high school and lost their first baby. But they persisted in getting through university, taking 5 or 6 years and having Noemi along the way. She is a bright healthy kid who loves school and her ballet lessons, living in a close family and village milieu with cousins, aunts and uncles, and grandparents, far from the hard reality of the Cañari diaspora in Queens, Newark, Minneapolis of the Bronx. With two professional parents, there is no question this Noemi will go to university, and she surely won’t need one of our scholarships. In only one or two generations, with educational opportunities, the lives of Cañari girls and women can be turned around.

Noemi is six or seven now. Her parents came from poor indigenous families that chose not to emigrate. Her father, Juan Carlos, a professional musician and teacher, and her mother Pacha married during high school and lost their first baby. But they persisted in getting through university, taking 5 or 6 years and having Noemi along the way. She is a bright healthy kid who loves school and her ballet lessons, living in a close family and village milieu with cousins, aunts and uncles, and grandparents, far from the hard reality of the Cañari diaspora in Queens, Newark, Minneapolis of the Bronx. With two professional parents, there is no question this Noemi will go to university, and she surely won’t need one of our scholarships. In only one or two generations, with educational opportunities, the lives of Cañari girls and women can be turned around.

I only wish the other Noemi had been given that chance.

As always Judy, a beautifully written and thoughtful post – and really important too. I do hope you made some headway with the village girls dreaming of life in Queens.

I read this article in the NYT and needless to say it was heartbreaking. Of course I too wondered if you knew the family.

I would like to share this on my Facebook page with your permission and with a link for your scholarship fund.

I read it and then looked over at Cisco lost in his iPhone texting away and it’s just another reminder of what could have been his future and what might be the future of so many others. A future that with people like you gives hope for change.

Incredibly, Judy. I was moved to tears, by the untimely death of Noemi but also by the good work you do. I read this beautiful piece aloud to George and he wondered what is it that drives so many of the Cañari north. Is it just lack of jobs and opportunity, or are there other factors?

Wow, what an amazing piece. With your permission, I will take it to my graduate class (Political Economy through a Feminist Lens) on Tuesday and share it with the other students. We are looking at exactly these issues around globalization, changing labour markets, etc.

yes, of course. And let me know the feedback. So you are in graduate course now? Let’s chat soon.

Yes, it is almost entirely lack of jobs and opportunity. The economy of Ecuador collapsed in 2000, and has never fully recovered. (Here, today, a daily construction works makes $10-$15.) No one wants to leave their family, their children, their country, their culture. But once they migrant they cannot come back without paying over again to return. So for those who choose to stay in the U.S. – they know they may never see their mother, sisters, father, brothers again. That is their sacrifice, and one they shouldn’t have to make. And for those parents who can’t bear the thought of never seeing their children? They put their hopes in the coyotes, pay great sums, put their children at great risk, all with the dream of reuniting the family. It sometimes turns out OK, but sometimes not.

Janice – let me update the scholarship link, and I’ll send it to you tomorrow or next day. Thanks.

Please e-mail the link to your scholarship fund.

Will do.

Such a touching story, Judy. It made me cry!

It also made me rethink my conversation with you about

“workers” available from an Ecuadorian community in Austin.

No words, really. I had no idea of the magnitude of young

people traveling alone. Thank you for this beautifully done piece,

though the news is sad

Love, you sister, Char

Judy, as for others, your blog post brought me to tears. It is utterly heartbreaking to imagine a child of this age, alone on such a dangerous and uncertain journey, headed toward a dead-end future in an environment far from extended family and familiar culture. I was so heartened (and impressed) that you headed pronto to Noemi’s home village to help paint a picture for an alternative future, based on educational opportunity. The scholarship fund you have spearheaded may have (literally) already saved many lives of young women who could’ve suffered fates like Noemi’s. It is good and important work and I am so proud to be your friend. Nancy

Thank you good friend Nancy.

Thanks Sister Char. I think that Noemi was not being brought to the U.S. to work. Her parents had been undocumented migrants in New YOrk for many years, with jobs, and my guess is they really wanted to reunite the family and send Noemi to school.

Querida Judy, estoy impresionada por esta noticia, aunque vivo en Costa Rica, un país chiquito y cada vez con menos oportunidades y aunque estoy interesada en las noticias importantes que suceden en América Latina, no había leído nada sobre esta noticia. Estoy muy impactada.

En la comunidad en donde yo vivo también tenemos muchos niños y niñas mjy pobres y trabajo con ellos dos veces por semana, tratando de abrir puerta de confianza y tratando de acompañarlos. Esta noticia me demuestra que tenemos que seguir trabajando para acompañar a nuestras nuevas generaciones con mucho o poco dinero, porque especialmente nuestras niñas y niños necesitan atención, cariño y oportunidades para vivir mejor. Estoy muy orgullosa de conocerte por ese trabajo que me inspira siempre. Gracias por tu cariño por esas jóvenes cañaris y por tu compromiso con la comunidad en donde vives. Recibe mi abrazo extendido a Michael también.

Lupe

This is such a devastating situation. I’m troubled that scenarios like this are on the rise. Thank you for communicating and offering real hope against this dark backdrop.

Gracias Querida Lupe! Estas en Costa Rica otra vez? Un abrazo, Judy (+ Michael, desde la cocina)

I just want to cry… for Noemi´s death, many Noemís, for how powerful nations attract the wish to live (and leave) strange adventures in the pursuit of…nothing that gears their lives towards Happiness. Thanks Judy and Michael for making possible other opportunities.

Alex

What a devastating story. But, the natural way in which you responded to the story – by going to Noemi’s school and trying to teach the girls about education – and giving them hope – that’s what brought me to tears. You are doing such wonderful work and I am moved by it. xxxLisa